Price elasticity of demand is the change in demand for a product resulting from a change in price. Demand will normally increase with a reduction price, but the magnitude of the increase can vary a great deal between different products and markets. Reversely there’s price elasticity of supply, which normally increases with increases in the price offered.

Volume of demand increasing as the price asked goes down

Volume of demand increasing as the price asked goes down

The time dimension

The relationship between price and both supply and demand will often change over time. For recurring and sustainable factors, the elasticity will typically grow in magnitude as more time passes, as suppliers or consumers have more time to respond and adjust to the change in price.

Price elasticity of grain

To illustrate the above concept, we’ll look into how to ease the increased production of an expanded grain farm into the market.

We have the potential to increase (double) production, but we also have a build-up of inventory. What will happen to the price, and our profits, when we increase the volume of sales.

Immediate demand

The current turn saw a volume of 94 grain change hands during the start-of-turn auction, at a price 3.14d each. If we wanted to sell more grain right now, that would match up against the pending demand on the market. We can sell up to 11 extra grain at a progressively lower price, down to 2.57d.

That doesn’t look like a good deal. With a production cost of 2.15d per unit, we’re currently seeing good unit economics. The extra volume from that sale wouldn’t make up for the reduction in profit per unit.

Who is the demand?

We prefer to focus on the long term though, and now the picture gets more complicated. We need to consider who is buying the grain and how they may respond to a reduction in price. The most predictable consumers are the Commoners of our town.

They currently consider grain slightly expensive relative to bread, and may adapt their spending pattern to consume more grain if the price became more attractive. (As a side-note, they are currently not doing well financially, and hiring more of them on our farm will improve their situation and allow them to buy more grain from us)

Also, grain is an input in production of bread. If grain becomes cheaper, it’s likely that more will be consumed by the town’s bakeries. This effect won’t be immediate though. Humans and bots alike take time to evaluate and respond to new market situations.

The bakery of a competitor. We can’t directly influence or predict their behaviour, but it’s reasonable to assume cheaper grain would tempt them to use more. If this is a human player, we can also simply ask what they think and perhaps strike up an agreement.

The bakery of a competitor. We can’t directly influence or predict their behaviour, but it’s reasonable to assume cheaper grain would tempt them to use more. If this is a human player, we can also simply ask what they think and perhaps strike up an agreement.

New sources of demand

Other than adjustments to existing demand, we should consider additional sources of demand for our increased grain output. Perhaps a lower price of grain will make construction of a brewery in the town viable? Or a new export route to a neighbouring town.

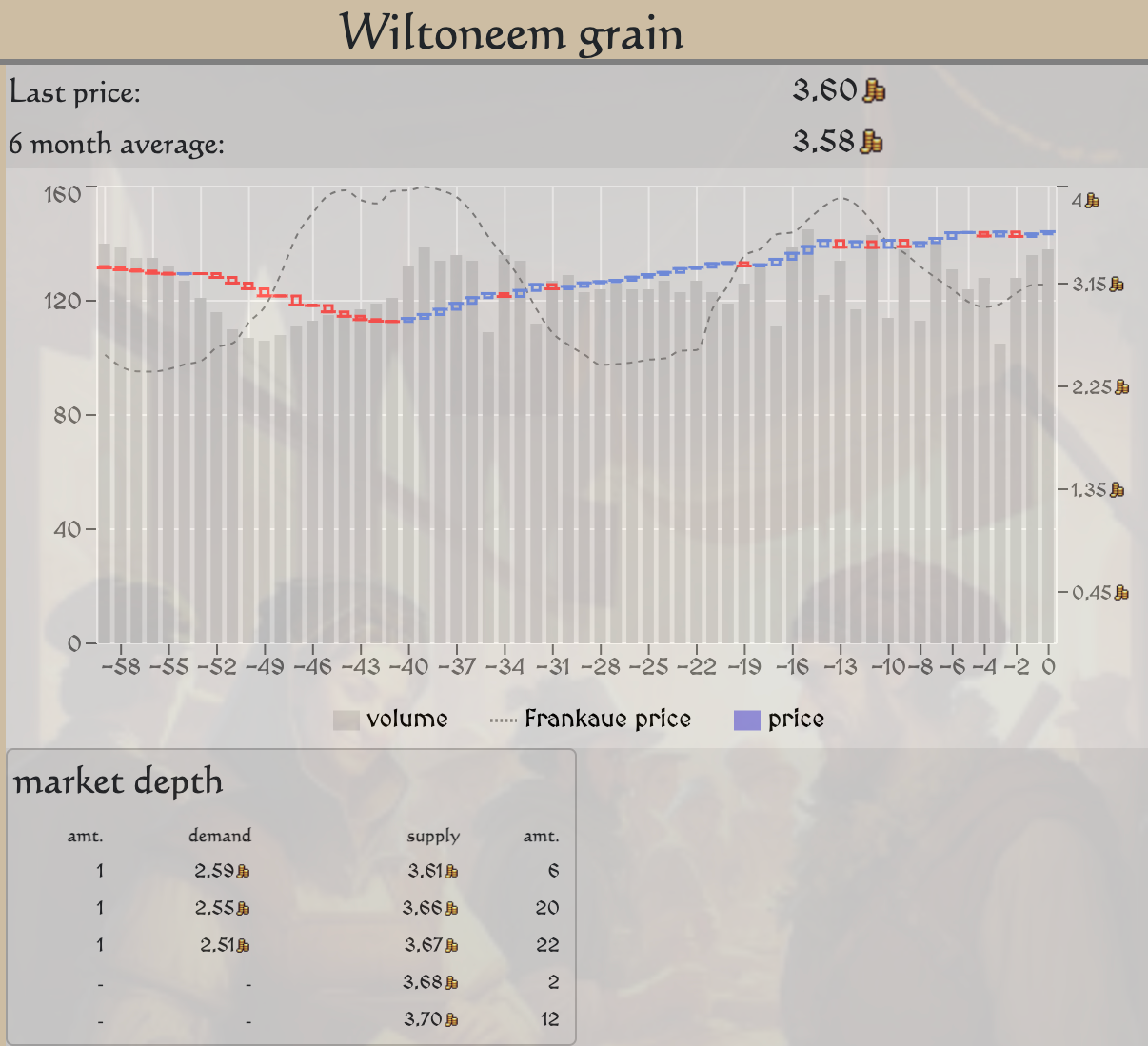

Neighbouring Wiltoneem provides additional demand for grain. Factoring this into our calculation would give a higher elasticity magnitude.

Neighbouring Wiltoneem provides additional demand for grain. Factoring this into our calculation would give a higher elasticity magnitude.

No exact science

Unfortunately long term projections are rarely accurate, but after considering the various factors you’ll get a sense for how the market may respond. Make the adjustment and check back later to see if any corrections are needed.

We decided to crank up the production and sales. We put the sales slightly above the production for now to burn down our output inventory and free up some cash.

The market had a dip in response to our sudden increase in sales, but quickly bounced back most of the way, and 9 turns later we’re getting 3.10d per unit, almost the same as before. Of course, the market and our farm don’t existing in isolation, and as we see on the previous history, prices can swing even without any changes from our side.

True markets versus simple markets

Mercatorio strives to simulate real market mechanics, giving rise to realistic behaviours like shown above. Markets are complex and sometimes unpredictable, and this is part of the challenge of building a successful business.

Many games prefer to tone down this aspect of markets and provide other kinds of challenges instead, like warfare or politics. We’ll use the concept of price elasticity to analyse a couple of them to highlight how Mercatorio is different.

Example A (Anno 1800)

Perhaps the simplest market is one where you get a price and no volume.

At this market you get $32 per ton of potato, regardless of how many you sell. There’s infinite demand.

In isolation you could scale up your potato production business infinitely to have endless profit, but the game counters this in other ways (space constraints and progressive taxes).

The same does limit supply through limited volume, again with no price sensitivity.

Timber costs $10 per ton and there are 150 tons available. After that, no supply is available at any price. There is however a time aspect, as supply is gradually replenished over time.

Example B (Victoria 3)

This game emulates supply/demand elasticity as price deviations caused by market (im-)balance.

There is a fixed reference price for each product, which the market price may deviate from. The concept of market balance, the surplus of supply or demand relative to the other, can be interpreted as the existence of a shadow market behind the one on display. With this interpretation, we can use the above table to calculate the price elasticities of that hidden market.

Eg. for fish, there are 977 sell orders and 788 buy orders, meaning the shadow market is absorbing 188 (sic) excess fish. This extra demand requires a discount of 17% from the reference price.

If we plot the market balance as a portion of volume against price deviations, we find a pattern:

This makes it straightforward to calculate the price effect of increased supply, each 1% gives a price reduction of 0.75% in the short term. In the longer term, as in Mercatorio, new consumers may come online and add to the buy orders, reducing the price deviation.

Embracing the challenge

Mercatorio elevates markets and their complexities to a core element of the game rather than replacing them with simplified variants. This give rise to some challenges you’d normally not come across in other games, as markets can be unpredictable and move quickly when the conditions change, akin to real world markets. In Mercatorio, navigating the markets is just as important as navigation of forests, seas or rivers, and one of the most important skills to master on your journey to becoming a powerful merchant.